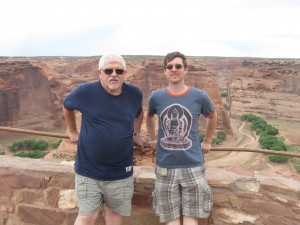

My dad and I went to see the Grand Canyon yesterday. But the photo on top of this article isn’t from there. It’s from the day before when we went to see Canyon de Chelly. The lady at the Welcome to Arizona place told us there were some cave dwellings there. So we went up to see those first.

My dad and I went to see the Grand Canyon yesterday. But the photo on top of this article isn’t from there. It’s from the day before when we went to see Canyon de Chelly. The lady at the Welcome to Arizona place told us there were some cave dwellings there. So we went up to see those first.

Unfortunately Arizona weather is freaky. As soon as we got there all these bizarre rain storms started happening. It seemed like it would rain over an area about half a mile across and kick up a big dust storm and then move on a couple minutes later. We didn’t want to hike an hour down to the cave dwellings and then get stuck there. So we just looked at the canyon from the rim. Anyway,we never got any photos together at the Grand Canyon itself. So I’m using this one for the top photo.

We looked at the Canyon De Chilly for a while and ate at the local Burger King, which was one of about four restaurants in the town of Chinle, Arizona deep inside the Navajo Reservation. Then we drove across the Hopi Reservation, which is inside the Navajo Reservation, to the town of Tuba City where we were told we could find a hotel to stay at so that we could proceed to the Grand Canyon the following day. The Hopi Reservation has its own radio station that plays songs that go “Hi-ya Hey-ya Oh-ya Hi-ya.” Some of them also have funny interesting lyrics in English as well. One went, “How come every time I think I find Mr. Right he turns out to be Mr. Five Kids on the Side?” These lyrics are chanted to the same melody as the “Hi-ya Hey-ya Oh-ya” parts. It was interesting.

Tuba City was a mystery to me. We found four hotels there. Two were sold out completely. One had only one room left but they wanted $162 for it. Finally we discovered a hostel called the Grey Hill Inn who charged us $65 for a room with two beds but no bathroom. The shared bathroom was down the hall. And it was decent. I’ve stayed in hostels lots before so it was no big deal. I thought it was nice. Though I am baffled that a town miles away from anything would 1) have four hotels, 2) be able to charge such high prices and 3) be full up even given points one and two. Tuba City is about two hours drive from the Grand Canyon and you can get expensive hotels right by the canyon itself if you want, so that can’t be the reason. It’s no closer than Williams or Flagstaff, both of which are way cheaper to stay in and have lots more stuff.

Anyway, we went to the Grand Canyon the day after our stay in Tuba City. It was cool. It was a big-ass hole in the ground. It was either shaped by erosion over the course of six million years or created just as it is today by God roughly four thousand years ago. Take your pick.

Anyway, we went to the Grand Canyon the day after our stay in Tuba City. It was cool. It was a big-ass hole in the ground. It was either shaped by erosion over the course of six million years or created just as it is today by God roughly four thousand years ago. Take your pick.

I have to say, though, that I am just not the kind of person whose breath gets taken away by amazing sights. I don’t know if this is a Zen thing or not. I think it might be. But I find pretty much every sight I see pretty amazing, even if it’s a Wal Mart where I’m trying to find something healthy to snack on in the produce section instead of eating Fritos from a gas station. The Grand Canyon is a lot prettier, for sure. And there’s something to be said for that. I’m just not one of those people who pees themselves with delight upon seeing that sort of thing.

This doesn’t mean I regret going. I’m really glad I went. I’d hate to miss out on something as cool as seeing the Grand Canyon, especially when it was pretty much on my way out to California anyhow. And being with my dad was really nice. The title of this article isn’t really my opinion. The Grand Canyon does not suck. It rules. Allow me to attempt to explain.

It’s interesting what happens when you stop dividing life into that which you consider mundane and which takes up about 98% of your experience and that which you consider either bitchen cool or incredibly horrible, which takes up about 2% of your life. It doesn’t make the spectacular stuff like the Grand Canyon any less spectacular. Instead it makes everything you encounter spectacular.

Yet to the untrained eye, it might seem like you’re unimpressed, like you think, for example, that the Grand Canyon sucks (hence the title of this piece). It’s not that I’m unimpressed by the Grand Canyon. It’s just that if I went “OMYGOD!! LOOK AT HOW GREAT THAT IS!!!!!” every time I felt like that about something, they’d cart me away to the Happy Home.

***

I will be speaking at Empty Sky Zen Center near Phoenix, Arizona on tonight, Friday June 29th at 7pm. The address is 5246 E McDonald Dr., Paradise Valley, AZ 85253. If you’re not a regular there and wish to attend please send an email to Ann Baker at anbakrann@gmail.com. They just need to get a head count. Newcomers are very welcome. This is not an “advanced” sitting.

“…words revealing the Small Vehicle obsession with personal liberation, rather than throwing oneself into the world, manifesting joy and compassion.”

Joy and compassion are incompatible with craving. There is no such thing as “personal liberation”, there is only the cessation of craving, which manifests as unconditional love. Who knows, if you ceased to crave, you might even learn to love Theravadins.

Mark, who really knows if there is such a thing as permanent cessation? Even if the Buddha were staring you in the face, you couldn’t tell for sure. Just know dukkha, and tanha, and yourself. That should be enough.

“I thought this was a zen blog. What’s with all the hinayana sophistry clogging the posts??”

Brad criticized a mahayana teacher online. Maybe this is his karma? 🙂

BY, in Tibetan Buddhism they use the term “nirvana” in several ways: first, to refer to the state of a mindstream that no longer has the causes to experience mental afflictions, and second to refer to ultimate reality. But they describe ultimate reality in negative terms, not as a positive thing. IOW, it’s a fact about reality, not a physical or even a mental thing. It’s a thing one can have an awareness of, but not awareness itself, although when you have a clear awareness of it, the awareness of the distinction vanishes.

Mark said:

“. I was reading Chadwick’s interview with Katherine Thanas, who just passed away, and she said that she compared notes with Shunryu Suzuki and they both had enlightenment experiences that lasted about two weeks (cuke.com/Cucumber%20Project/interviews/thanas.html)”

However,

“In Shunryu Suzuki’s book the words satori and kensho, its near?equivalent, never appear.

When, four months before his death, I had the opportunity to ask him why satori didn’t figure in his book, his wife leaned toward me and whispered impishly, “It’s because he hasn’t had it”; whereupon the Roshi batted his fan at her in mock consternation and with finger to his lips hissed, “Shhhh! Don’t tell him!” When our laughter had subsided, he said simply, “It’s not that satori is unimportant, but it’s not the part of Zen that needs to be stressed.”

Why not? Without experience, words are hollow expressions of duality.

“although when you have a clear awareness of it, the awareness of the distinction vanishes”

There is no you to have a clear awareness of it, because that which is doing the

seeing is enlightment seeing itself.

So you could say that Suzuki is right in that the man, the zen master before you,

doesn’t experience satori.

BY, I’ve experienced intense joy and compassion because of, in spite of and regardless of my cravings, and plan on continuing to do so until the day I keel over and wake up in Nirvana Inc.

“There is no you to have a clear awareness of it, because that which is doing the

seeing is enlightment seeing itself.”

If it’s not my awareness to which the experience of ultimate reality appears, what good is it? Who is this “enlightenment” who has the experience, and why does it rate?

“BY, in Tibetan Buddhism they use the term “nirvana” in several ways: first, to refer to the state of a mindstream that no longer has the causes to experience mental afflictions, and second to refer to ultimate reality. But they describe ultimate reality in negative terms, not as a positive thing. IOW, it’s a fact about reality, not a physical or even a mental thing. It’s a thing one can have an awareness of, but not awareness itself, although when you have a clear awareness of it, the awareness of the distinction vanishes.”

The term Nirvana simply means “blown out”, referring to the “fire” of tanha, craving, seeking for satisfaction, etc. It is a negative reference, not a positive one. It doesn’t even infer what remains after the fire is blown out. As with TB, most non-dual traditions only describe ultimate realization, and ultimate reality, in negatives. If they use positives, they are generally all forms of infinity, or ati, or “beyond”, which in the end only comes down to things the mind can’t possibly comprehend. Thus, still a negative description in the end.

You can of course give it a positive name, but that’s all it is, a name. You can call it “transcendental consciousness” as Hindus do, but that doesn’t really tell you anything.

It doesn’t mean you can’t talk about what is there when the fire of tanha is blown out or quenched, but it does mean that anything you say is going to be inadequate and probably misleading in some respect. That’s why the emphasis in most of Buddhism is on the practice of blowing out the fire, rather than describing what Nirvana is like experientially, since that’s not really possible.

Sure, call it the mindstream that is no longer affect by tanha or its effects. But what would that be? You can’t really say. The problem isn’t that in Nirvana there is no awareness of Nirvana, in the sense of being ignorant of it. It’s simply that there is no distance between oneself and Nirvana, and one knows it so directly that there’s no mind or state to get in the way. It is you, whoever or whatever you are. It is absolutely certain in that sense. And there’s really no need to describe it, or even much point in trying. The only thing one could do in that position is teach people how to blow out the fire of tanha, so that they can know it directly also. Which is what Buddha did. I’m not sure if anyone else has ever done more than that, regardless of which yana they are teaching.

“BY, I’ve experienced intense joy and compassion because of, in spite of and regardless of my cravings, and plan on continuing to do so until the day I keel over and wake up in Nirvana Inc.”

Sounds like a plan. But what makes you think you’ll ever wake up in Nirvana by pursuing it? You do know that everyone who has ever lived has experienced intense joy and compassion many times throughout their difficult lives? That doesn’t lead to Nirvana, just to more of the same. Which is fine if that’s what you want. That plan just keeps us spinning on the endless wheel of cravings, experiencing whatever the craving life has to offer, including joy and compassion from time to time.

Nirvana, the cessation of craving, is the last thing you’d ever want, especially when craving seems so fascinating and profitable. It doesn’t just happen to you. So don’t count on just waking up someday. It will literally never, ever happen. You have to take a bucket of water and douse that fire. Otherwise, it just keeps burning.

But really, who cares? You clearly don’t, so there’s no loss. Nirvana is just a rock band, after all.

BY, I think what this illustrates is that you should make your responses as simple as possible, and no more simple than that. What you just said accords exactly with my understanding; what you said earlier just sounded like nonsense. :}

I’ll agree with you, BY (and Ted) that the cessation of Craving (with a capital “C” in the Pali Text translations) is synonymous with never-returning in the Gautama’s teaching as we have it in the four principal Nikayas, and that seems to have been what he took as the utmost of well-being. I find it interesting that he broke Craving down as:

“… that craving that leads back to birth, along with the lure and lust that lingers longingly now here, now there; namely, the craving for sensual pleasures, the craving to be born again, the craving for existence to end.” (SN V 420-422, Pali Text Society volume 5 pg 357)

I see these three aspects of craving as the counterparts to “that which we will…, and that which we intend to do and that wherewith we are occupied (-this becomes an object for the persistence of consciousness)”.

I do have a reservation about this, BY:

“That’s why the emphasis in most of Buddhism is on the practice of blowing out the fire, rather than describing what Nirvana is like experientially, since that’s not really possible.”

I have read that the literal translation of nirvana is “blown out”, but here’s my concern about an emphasis on a practice of blowing out- if that which we will, and that which we intend to do, and that wherewith we are occupied becomes an object for the station of consciousness and leads to ill, then Craving may be blown out but as Fred would say, there is no I, no “mine the doer” that blows.

There’s a lecture somewhere where Gautama asks the monks what interval of practice they utilize, and while some answered months and others weeks or days, the monk whose answer Gautama favored said “one breath”. The breath by which Craving is blown out, just in one, perhaps?

‘Nirvana, the cessation of craving, is the last thing you’d ever want, especially when craving seems so fascinating and profitable. It doesn’t just happen to you. So don’t count on just waking up someday. It will literally never, ever happen. You have to take a bucket of water and douse that fire. Otherwise, it just keeps burning. But really, who cares? You clearly don’t, so there’s no loss. ‘

Actually I do care, very much. But idle speculation about what it all means or, even worse, fashioning a strategy (and its inevitable ego-identity) to achieve this strikes me as missing the point.

I don’t count on just waking up someday because it’s all NOW. Are my cravings right now causing me and/or others trouble? If so I let them go and wake up to this moment. If not I don’t worry about them and wake up to this moment.

When people say I make sense, it makes me very suspicious of both of us.

“Actually I do care, very much. But idle speculation about what it all means or, even worse, fashioning a strategy (and its inevitable ego-identity) to achieve this strikes me as missing the point.”

Yeah, I guess when the Buddha fashioned his Noble Eightfold Path for the undoing of craving, it was all just about strengthening his ego-identity.

This isn’t idle speculation, it’s simply taking the notion of the cessation of craving seriously. To do that, you have to realize that this is the heart of what Buddhism is actually about. The rest of it is just stylistic differences. And to take it seriously means actually doing what works to bring about the lessening and eventual cessation of craving. That requires study, discipline, meditation, right conduct, sadhana, the full eightfold path. There is no other point. If you think you can cease to crave by some other means, fine, let’s hear about it.

“I don’t count on just waking up someday because it’s all NOW. Are my cravings right now causing me and/or others trouble? If so I let them go and wake up to this moment. If not I don’t worry about them and wake up to this moment.”

Well, are you awake now? Have you ceased craving now? If not, why not? Perhaps it’s because you aren’t taking the actual practice of Buddhism seriously. If you let go of these cravings, and they still come back, what are you going to do about that? Just not worry about it all?

There actually is a path for dealing with these issues in a very disciplined and straightforward manner. You might give it a try.

Mark,

Yes, I really like all of those comments. Particularly about the “one-breath” cycle.

It is certainly the case that the craving for the cessation of craving must also cease. But it ceases not by just forgetting about spiritual life and kicking back with the ordinary cravings of life intact. It means surrendering even this craving, and having disciplines in place that keep that craving from becoming a controlling force in our lives.

Which rather brings to mind the recent posts about the Diamond people in New Mexico, and their obsessive practice that seems determined to try to bring about enlightenment as quickly as possible. This is the kind of excessive discipline that itself needs to be disciplined. It’s actually counter-productive to unleash the craving for enlightenment in that fashion, in that it simply ends up deluding us even further. So even discipline must be disciplined, and craving released no matter what kind of seemingly noble cause it is meant to serve, even if that cause is enlightenment itself. This, because true enlightenment is freedom from craving, not the result of fulfilling one’s craving for enlightenment.

As I said before, enlightenment is not satisfying. It does not satisfy the craving for enlightenment. It is the cessation of all craving. There isn’t some kind of enlightenment that we can attain, that will satisfy the craving for enlightenment. Whatever we attain, we will still crave an even greater enlightenment, because that is the nature of all craving. It’s endless. We can never have enough money to satisfy our craving for money, and we can never have enough enlightenment to satisfy our craving for enlightenment. The solution is to no longer crave either, and to find in that cessation of craving a very different kind of enlightenment than we thought we would ever find through our cravings.

BY, I think when you start to talk about what enlightenment is and is not, you are treading a path between two steep dropoffs, and you need to be very, very careful of your footing.

Craving in my lineage is described as “ignorant wanting.” Ignorant meaning not understanding how things arise. You can’t simply say that a Buddha doesn’t want things, because that would necessarily mean that he or she wouldn’t teach. What you would understand is that the Buddha doesn’t misunderstand how things happen, and so when the Buddha acts, the Buddha acts spontaneously with perfect understanding of cause and effect.

The practice at Diamond Mountain is simply to do nothing but sit, eat, sleep, shit and study for three years. If you consider any of these practices to be a punishment, then of course this is wrong, and shouldn’t be attempted. If on the other hand you see them either as potentially fruitful, or as something to be enjoyed in themselves, then it seems to me that they are no different than any other thing you might do for three years. I’ve worked at jobs for three years that demanded as much of my time as a three year retreat, and what did I have at the end of the three years? An older body, closer to death, and some junk that I’ve probably already thrown out.

The interval of practice of one breath really says it all. If your interval of practice is one breath, then you just do the practice in each moment. This might lead you to a retreat in a cave. It might lead you to take on a lover, and begin a family. Neither is wrong, but both are different.

I see something sad.

It’s “new” Hardcore Zen sucking

A dead dog’s rectum.

Ted,

Defining enlightenment as “the cessation of craving” is simply using Buddha’s own definition of nirvana. I’m not trying to define it in any other way, stylistically or positively. It is what it is. It’s just not achieveable through craving enlightenment, unless one simply gets so sick of craving enlightenment in the process that one just gives up on that approach.

There is indeed a difference between craving and fulfilling ordinary needs. Eat when you are hungry, drink when you are thirsty, is not craving. As for Buddha wanting to teach, he didn’t actually want to do that. He did it out of compassion for all beings, not out of personal want or need or craving for attention and status and fulfillment. If one acts out of compassion and love, and gives up all identification with the results of one’s action, that is not acting out of craving. That is enlightened action.

That is why one is encouraged to take the Boddhisattva vow in many schools. It makes the motive to practice one of love and compassion, rather than some desire to fulfill one’s craving for personal enlightenment. This is done because the craving motive will never result in enlightenment, but only in some mind-created spiritual delusion. I think we can see plenty of examples of that around.

As for Diamond Mountain, I have no experience there, I know only what I have read. But it does seem apparent that Michael Roach and his followers were pursuing a very macho, results-oriented path that tries to attain enlightenment as quickly as they can. I think there are some pretty obvious errors in their approach from what I’ve heard, but I could be wrong. I would attribute those errors to trying to make Buddhism a path that will fulfill spiritual cravings, rather than surrender them. Such an approach always leads to escalating forms of delusional spiritual seeking, and often ends badly. I think it’s important to speak out against that sort of approach, even when it seems less extreme. But I understand that you naturally feel a bit defensive in regard to Diamond Mountain.

So take Diamond out of the equation if you like. The principle is still a true one, I believe. Apply it as seems fit.

“I see something sad.”

Very good. You are on the right path.

Ted, why do I like this: “An older body, closer to death, and some junk that I’ve probably already thrown out.” Ha ha!

Genpo points out that Zen is a school of sudden enlightenment, and the sixth patriarch was a wood-cutter who had such an experience when he heard the Diamond Sutra read out loud (he himself was illiterate).

For me, I have studied a lot, and I pretty much use it all every time I sit down to sit. However, all of it has now come down to where consciousness takes place as I wake up or fall asleep, and an ability to feel what is really referred sensation at the surface of the skin.

“Good morning, where am I?”- Sasaki at Mount Cobb in 2011.

Here’s a funny experience I had you might like, BY: about a month ago, I came down with a cold, and the second night I woke up frequently and had occasion to focus on my sense of location to get back to sleep. In the morning while I was sitting, I fell asleep briefly and then woke up; as I woke up, I realized that my sleep of a second or so had been completely dreamless (usually when I sleep sitting up I am aware of brief snatches of dreams as I wake up). I thought to myself, “what fun is that, no pleasant dreams, no nothing!”.

Later I thought, maybe that was an advancement for me in terms of being relaxed and calm in the posture, and certainly it was a stark insight into how much I like the pleasant things of this life.

I have noticed that the only two things the Gautamid advised to do in his “setting up of mindfulness” practice were “relax the activity of the body (with the in-breath, or with the out-breath)” and “calm the activity of the mind (likewise with the in-breath, or with the out-breath). As to all the other practices he advised, including the eight-fold path, the four arousings of mindfulness, the four right efforts, the four bases of psychic power, the five controlling faculties, the five powers, and the seven links in awakening, he said they all go to development and fulfillment through knowing and seeing things as they really are with respect to the six senses:

“(Anyone)…knowing and seeing eye as it really is, knowing and seeing material shapes… visual consciousness… impact on the eye as it really is, and knowing, seeing as it really is the experience, whether pleasant, painful, or neither painful nor pleasant, that arises conditioned by impact on the eye, is not attached to the eye nor to material shapes nor to visual consciousness nor to impact on the eye; and that experience, whether pleasant, painful, or neither painful nor pleasant, that arises conditioned by impact on the eye—neither to that is (such a one) attached. …(Such a one’s) physical anxieties decrease, and mental anxieties decrease, and bodily torments… and mental torments… and bodily fevers decrease, and mental fevers decrease. (Such a one) experiences happiness of body and happiness of mind. (repeated for ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind).

Whatever is the view of what really is, that for (such a one) is right view; whatever is aspiration for what really is, that for (such a one) is right aspiration; whatever is endeavour for what really is, that is for (such a one) right endeavour; whatever is mindfulness of what really is, that is for (such a one) right mindfulness; whatever is concentration on what really is, that is for (such a one) right concentration. And (such a one’s) past acts of body, acts of speech, and mode of livelihood have been well purified.” (Majjhima-Nikaya, Pali Text Society volume 3 pg 337-338, ©Pali Text Society)

Sorry, Khru.

Don’t apologize, friend.

Reading these posts causes me to have regular, daily bowel movements.

Ignoring BY’s pendantic condescension, I will instead throw some zen into the mix:

‘Some Buddhists say that nirvana (enlightenment) is the complete extinction of delusion and craving, and zazen or meditation is practiced in order to reach this state. However, if we assume this type of enlightenment to be the truth of human life, then this is nothing but saying that the truth of life is lifelessness, or death! Since cravings existing in human life are the cause of suffering, such Buddhists struggle to extinguish them and attain the bliss of nirvana. But isn’t seeking to get rid of pain and to attain the bliss of nirvana itself a delusion or craving? Actually, this too is craving, and precisely because of that the practitioner is caught in self-contradiction and can’t escape suffering. This is why Dogen Zenji said, ‘The practice of the buddhas and patriarchs is completely different from the way of hinayana’, and it is why he quoted from an earlier ancestor [Nagarjuna] about not trying to follow a limited form of zazen as self-control.

‘The zazen of the buddhas and ancestors, the zazen of the reality of life, is not like this. Since desires and cravings are actually a manifestation of the life force, there is no reason to hate them and try to extinguish them. And yet, if we become dragged around by them and chase after them, then our life becomes fogged over. The important point here is not to cause life to be fogged over by thoughts based on desires or cravings, but to see all thoughts and desires as resting on the foundation of life, to let them be as they are yet not be dragged around by them. It is is not a matter of making a great effort not to be dragged around by desires. It is just waking up and returning to the reality of life that is essential.’ -Kosho Uchiyama, Opening the Hand of Thought.

Thanks, buddy.

And here’s an excerpt from Shobogenzo Chapter 95, HACHI-DAININ-GAKU: The Eightfold Awakening of a Great Human Being, translated by Mike Cross ( http://www.the-middle-way.org/subpage32.html )

Every buddha is a great human being. That to which a great human being awakens is therefore called the eightfold awakening of a great human being. To awaken to this teaching is the cause of nirvana.

It was the last instruction of our Original Master, Sakyamuni Buddha, on the night that he entered nirvana.

1. Wanting little

The Buddha said, “You beggars should know that people of big desire and abundant wants abundantly seek gain, and so their cares also are abundant. A person of small desire and few wants, being free of seeking and free of wanting, does not have this trouble. Small desire, wanting little, you should practise just for itself. Still more, wanting little can produce all kinds of benefits: People of small desire and few wants have no tendency to curry favour and bend in order to gain the minds of others. Again, they are not led as if they were enslaved by the senses. Those who practise wanting little are level in mind; they are without worries and fears; when they come into contact with things they have latitude; and they are constantly free from dissatisfaction. Those who have small desire and few wants just have nirvana. This is called ‘wanting little.’ ”

2. Being content

The Buddha said, “If you beggars desire to be rid of all cares, contemplate contentment. The teaching of knowing contentment is the very place of plenty, ease, and peace. A person who is content, who knows satisfaction, even when lying on the ground is still comfortable. Those who are not content, who do not know satisfaction, even when living in a heavenly palace are still not suited. Those who do not know satisfaction, even when rich, are poor. People who know satisfaction, even when poor, are rich. Those who do not know satisfaction are forever being pulled through the five desires, as if they were slaves; they are pitied by those who know satisfaction. This is called ‘being content.’ ”

Not no desire. Small desire.

Buddy,

To repeat, nirvana is not a state, even a state of “non-craving”, any more than the beautiful sunny day outside is best described as a “state of non-raining”. The absence of rain does not define the day, and the absence of craving does not define enlightenment. The sun that shines when craving is no longer clouding our day is obvious to the enlightened, but almost impossible to imagine to someone who has always lived in cloudy weather and never seen the sun. If you told them about a sunny day, they would have no idea what you were talking about. If you told them it was a day without clouds in the sky, they would at least have a clue, but still no real sense for it.

You can’t define a state negatively, and expect much sense to emerge from that description. It defines the path, not the result. The elimination of craving is the path, but the result is not some “craving-free state”. The result is more akin to a “sunny day”.

The purpose of zazen is indeed to help us see the futility of craving, and eliminate them. But the result is a sunny day. When the clouds vanish, they no longer define us.

Is life defined by craving? Well, as long as we crave, it is. But if we cease to crave, we see that it isn’t. It’s defined by what is naturally the case when cravings cease to define us. Call that “sunlight” if you wish. The notion that life can’t be lived without craving is like a dweller in an endlessly cloudy world claiming that life can only be defined by the shape and color of clouds. Anything else is impossible. But part those clouds, and a very different world opens up. It was always there, but our insistence on the inherent existence of clouds prevented us from seeing what was there.

Tanha, craving, is not the same as the word “desire”. It refers to mental craving, not the ordinary desire we have as living creatures for our ordinary needs. So I think when this passage refers to “small desire”, this is what is being referred to. “Big desire” would be a reference to the ever-growing desires our minds dream up.

As for the reference to “contentment” and “satisfaction” in the second paragraph, I would consider this a reference to the notion that rather than seek contentment of satisfaction of our cravings, we should simply practice being already content and satisfied. This is a good practice for those who are addicted to craving these ends. I would recommend it. It does indeed leave to the elimination of our cravings. But in nirvana, even this is extinguished. In nirvana, there is neither contentment nor discontent, neither satisfaction nor dissatisfaction. These dualisms have been extinguished along with craving itself.

That’s how I understand these teachings, at least.

“Small desire” – SHOYOKU, from the Sanskrit alpecchuH (alpa: small, minute, trifling + icchuH: wishing, desiring). Monier-Williams’ Sanskrit Dictionary defines the compound thus: “having little or moderate wishes.”

“Contentment” or “satisfaction” – CHISOKU [‘to know satisfaction’] from the Sanskrit saMtuSTaH (sam; together/completely [= an intensive prefix] + tuSTa: quite or well satisfied or contented, well pleased).

– assembled from notes to the N/C transaltion of SHOBOGENZO, definitions from the MW Dictionary, and my own Sanskrit studies.

Nirvana – “Seeing one thing through to the end” (S.Suzuki).

I hope that helps.

Dictionary definitions are nice, but they don’t convey the full meaning in context.

As for this:

Nirvana – “Seeing one thing through to the end” (S.Suzuki)

Well, that’s not Buddha’s definition, so I’m not sure what religion Suzuki was practicing.

You mean if I play World of Warcraft all the way through to the end, I’m in nirvana?

That’s a funny one, that S. Suzuki quote.

Helps me to take my thoughts as positive if I recognize they are an absorption, just as sleeping sitting up is an absorption, and even experiencing the location of consciousness while falling asleep or waking up is an absorption. When I realize an absorption, I have seen one thing through to the end, or maybe I’ve seen “things as they is” to the end- another Suzuki quote.

Brings up the question, does that which I will, that which I intend, or that wherewith I am occupied break the absorption? In other words, is my everyday experience a kind of nirvana before ignorance kicks in to station consciousness, and give rise to grasping in the five groups?

‘Well, that’s not Buddha’s definition, so I’m not sure what religion Suzuki was practicing. ‘ Ah, I see BY suffers from the ‘Buddha says it, I believe it, that settles it!’ olde tyme religion syndrome. You do realize that the recorded words of the Buddha were as likely conceived by his disciples as by him? And at any rate they are formative, not normative. As with any authentic wisdom tradition, truth is gaged, not by the identity of the author, but by the transformative resonances created.

Buddy,

I like Buddha’s approach to authority, which is the old, “Examine it for yourself, and if it agrees with reason, sense, experience…” I think you know the quote.

I’m not claiming Buddha is right, and Suzuki wrong, just that they aren’t saying the same thing, and Buddhism is pretty much defined by what Buddha taught (with plenty of room for creative elaboration), not by what Suzuki taught (or Dogen, for that matter). Maybe Suzuki had the better understanding of nirvana. I’m not really qualified to judge. It’s just not what Buddha taught. Call it “Suzukism” if you want, not Buddhism. If it works for you, go with it. Just don’t feel obliged to call it “Buddhism” as if without that label it’s somehow lacking.

But I’m just joking anyway, like Suzuki probably was. He was probably just sick of people asking him what nirvana was, so he gave some dumb-ass contrarian answer just for the hell of it.

Personally, I could give a rat’s ass what Buddha actually taught. I don’t take Buddhist teachings as authoritative, as most could probably tell. The parts that make sense to me, I embrace. The parts that don’t, I try to keep an open mind about. And the parts that seem downright stupid, I don’t hesitate to reject. Like you say, if it resonates, I run with it. But I also keep in mind that the parts I reject might well be the truest parts of all.

And quite honestly, I prefer Ramana’s and Nisargadatta’s Advaita to Buddhism. But there’s some great sense in Buddhism as well. Especially those Four Noble Truths. Gotta love that shit.

They learn recipes

But they do not prepare food,

Nor do they eat it.

So the dictionary definitions didn’t help, BY? I’ll try again.

Earlier you speculated on what exactly Dogen meant by ‘Small desire/wanting little’ and ‘being content/satisfied’ in the excerpt I quoted above. I suggest the meaning of these terms should be clear to anyone. From ancient India to medieval Japan to the modern English-speaking world ‘wanting little’ and ‘being content’ are universally understood. Hence – as demonstrated by the definitions I gave – they can be easily translated from one language, one time, one culture, to another.

On the other hand, there are philosophical/religious terms which can’t be so easily understood or defined, for some people take them to represent phenomena not found in everyday, universal experience. Taken this way, such expressions serve as material for idle speculation and dispute, and that’s all. If these terms are to have any real meaning for real people they have to be understood as they might relate to real life. This is the aspect of the Buddha’s teaching which Zen Buddhism emphasises. Hence Suzuki’s nirvana ‘joke’ – and very many other Zen ‘jokes’.

anon108,

I gave my interpretation of ‘wanting little’ in relation to nirvana. You obviously don’t like it. Seems like you think everyone ought to agree with your view on the subject. That’s a pretty big want.

Here’s a Zen joke:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LFFMtq5g8N4

“Wanting little” is just the yogic practice of santosha. I think it’s important to be aware of this, because it disabuses us of the notion that merely wanting little can lead to nirvana. If wanting little could lead us to nirvana, it would have worked for prince Siddhartha and the five ascetics would surely have attained nirvana through their ascetic practices, and the whole rest of the Buddha’s story need never have happened.

Santosha is important because it frees us from the distraction of trying to build a perfectly comfortable meditation space rather than meditating, and the distraction of trying to find the perfect foods to eat in between practice sessions, instead of practicing, and the need to get all the flies out of the meditation room before meditating, instead of meditating, and so on. If you don’t have santosha, you can never practice, and if you never practice, you will never get any results.

TGC, good point, although if one never learns how to prepare food, one will always be at the mercy of those who can.

“…Seems like you think everyone ought to agree with your view on the subject…”

I can’t deny it, BY. Sounds like Nirvana.

Not gonna happen though, is it 🙁

“You do realize that the recorded words of the Buddha were as likely conceived by his disciples as by him?”

I personally don’t think so. I have not found a counterpart to the teachings contained in the first four Nikayas for detail and consistency, although there are parallel teachings in other scriptures. Especially the consistency argues to me that the teachings were delivered by one individual.

In “Indian Buddhism”, A. K. Warder speaks to the history of the Pali Canon through the study of correlations in the Nikayas held in Southeast Asia, Tibet, and China. His conclusion, and I believe the conclusion of most of the other scholars who have studied the matter, is that the first four Nikayas probably do represent fairly accurately the teachings of the Gautamid (who was later called the Buddha).

The fifth Nikaya and the whole of the Abhidhamma are later compositions. Many of the famous scriptures of Buddhism, like the lankatavara, diamond, and lotus sutras, are much later compositions ascribed to the Buddha. I’ve tried to read them, but to me they are not positive and substantive, and I can’t use teaching by negation.

Ted,

Thanks for the clarification on Santosha. Sounds correct to me. I too think it’s important to reduce one’s wants in order to have room for practice. But for me, actual practice, such as sitting, means allowing myself to feel the truths of dukkha and tanha as deeply and intimately as possible. Zazen for me isn’t about staring at a wall, it’s about feeling the basic inner dissatisfaction and craving that I suffer and try to distract myself from otherwise. Allowing myself to feel and experience these directly and non-conceptually, and to do nothing in response but sit, is the best way to help reduce them, strangely enough. To feel the craving for peace and not act on it, is the best way to actually find peace, even if in the process I feel the inner warfare of my own cravings overwhelm me.

I agree that “little wants”, while a helpful approach, does not directly address the issue of craving. The second and third noble truths do not differentiate between “big tanha” and “little tanha”, and only advocate eliminating the first while preserving the second. It says to eliminate all tanha. Of course, it’s best to start by eliminating the big stuff. And it’s also important to differentiate tanha from ordinary bodily needs. It’s important to differentiate the hunger we feel for food necessary for our bodily needs, and the hunger for food that satisfies our unnecessary, conceptual and existential cravings. The first does not lead to dukkha, but the second does. And the same goes with everything else in life. As the Rolling Stones say, you can’t get no satisfaction, but you can at least get what you really need. Our problem is that we think we need things that we don’t, and spend a lot of energy trying to fulfill needs that can’t ever be satisfied.

Anon108,

Yeah, that’s it in a nutshell. We ain’t gonna get that kind of nirvana. But we might find that the nirvana we do get from letting go of our cravings is actually much better than the one we imagined that would come from satisfying our cravings.

That is interesting, Ted. It may well be that the Buddha is referring to the yogic practice of saMtoSa in the The Eightfold Awakening of a Great Human Being. But it’s very unlikely, I think, that Dogen understood it that way – as a particular meditative practice – for he never described or advocated such practices himself.

As BY suggested earlier, Dogen’s Zen may in many respects be different from what the Buddha taught. There are, of course, Buddhists who argue that Zen is not Buddhism at all. Fair enough. I like this bit from The Lotus Sutra:

“The Buddha’s equal preaching

Is like the one rain;

[But] beings, according to their nature

Receive it differently,

Just as the plants and tress

Each take a varying supply.”

And all the while Awakening no.8 is wagging its long finger at me –

“8. Not being wordy

The Buddha said, “If you beggars engage in all kinds of tittle-tattle and rambling discussion, your own mind will be disturbed. Although you have left home, still you will be unable to get free. For this reason, beggars, you should quickly throw away that wordiness which disturbs the mind. If you want to enjoy the ease that comes with extinction of cares, you should well and truly cut out the fault of idle discussion. This is called ‘not being wordy.’ “

BY, sorry if I was a dick on this thread, although it was worth it if my snipes in any way influenced your last post. Finally what you’re saying rings simple and true for me. Thanks for having the patience to keep at it.

Buddy, no problem. If being a dick were a crime, I’d be serving a life sentence (and maybe I am). Sometimes being a dick is even a good thing, if it forces us to get down to the nitty-gritty. I enjoy it when people are challenging. So thanks, really.

Anon108,

Yeah, wordiness can be a problem for me too. But I don’t know that Buddha was referring to serious dharma discussion. He seems more to be warning against idle blather and gossip.

But there really is an aspect of tanha which applies to dharma discussion, of the craving to be right, the craving to be seen as right, and even the craving to understand. It’s all got to be surrendered one way or another. It doesn’t mean we have to be silent, just attentive to that part of us which is trying to preserve our cravings rather than bring them to a close.

Dharma talk can definitely be idle talk, but idle talk is really any kind of useless talk—talk that we would be just as well off not having had, which is really most of what is said.

Santosha (your transliteration is noted, but the word isn’t pronounced that way) is not a meditative practice. It is a practice that you have to do to avoid avoiding meditation. I don’t know the fullness of Dogen’s teachings, so perhaps I missed that part, but I doubt that he failed to mention it to his students.

My experience of Dogen is that he is deliberately cryptic, so that each student will hear something different and useful from the same words. But a consequence of this is that it’s somewhat absurd to hold debates on the question of “what Dogen said.”

Correction re saMtoSa* not being a meditative practice noted. I made an ill-informed assumption about your reference to ‘yogic practice’.

I’ve read a fair amount of Dogen and had the benefit of having the meaning of much of it clarified by my teacher, a dharma-heir of Brad’s teacher, Dogen fan and translator Gudo Nishijima, for over 20 years. Familiarity with his style and philosophy de-mystifies a great deal of what might first appear “deliberately cryptic”. It seems very unlikely to me that Dogen would have regarded saMtoSa (merely) as “a practice that you have to do to avoid avoiding meditation,” although I don’t doubt that’s one of the benefits of such an attitude. Irrespective of what saMtoSa may have meant to Dogen, and more to the point, that’s not (merely) what “being content” means to me.

*I don’t mean to correct or ‘one-up’ your spelling of saMtoSa, Ted. ‘Santosha’ is a very good approximation of how the word sounds to an English speaker. But I prefer to use Harvard-Kyoto or Velthuis transliteration for Sanskrit rather than write it ‘as it sounds’ so that it’s clear to those with an interest and a little knowledge of the language exactly what word’s been discussed.

It also blows, but I’m quite fond of it. Lotsa beauty there if one knows where to look for it.

What is the point of transliterating a word into English, but not spelling it as it is pronounced? Is this some kind of scholarly preservation society trick to keep everything as obscure and unpronounceable as possible? They seem to do this a lot, all over the map. Check out Chinese names, etc.

Thanks for the background on Santosha. Thought it had something to do with the Hindu term used by Patanjali as one of his niyamas. Wikipeda gives a good summary of it here:

Santosha (skt. ????? sa?to?a, “contentment, satisfaction”[1]) is one of the niyamas of Yoga as listed by Patanjali.[2] Contentment is variously described, but can be thought of as not requiring more than you have to achieve contentment. It may be seen as renunciation of the need to acquire, and thereby elimination of want as an obstacle to mok?a.

The alternate spelling samtosha is also seen.

Seems like the same word and meaning. That’s also the purpose I had ascribed to it. Don’t know if the Buddhist version differs much. But it would seem to have been derived from a Hindu yogic practice.

OTOH, it doesn’t seem like Patanjali’s Santosha is the same as “little wants”. Patanjali’s method isn’t to reduce wants in order to make us more easily satisfied or content. but to simply abandon the whole notion that one can acheive satisfaction or contentment through any indirect method, and simply practice them outright, regardless of circumstances. This has the intended effect of eliminating all wants, by practicing the result immediately, rather than practicing something else, in the hope that it will bring satisfaction. It has the attitude of accepting everything we experience as it is, and not judging it by whether it brings us satisfaction or contentment, but seeing contentment and satisfaction as practices, rather than the result of other practices.

Whether the practice of contentment actually produces permanent contentment, or the practice of satisfaction actually brings permanent satisfaction, seems besides the point. The purpose is to eliminate the craving for these, and reduce the striving that produces negative forms of seeking.

BY, correct, it’s one of the niyamas, which are one of the eight limbs of yoga, which were taught by Patanjali, among others. The Buddha studied with early yogis before his enlightenment, so there’s a strong connection between the yoga lineage and the Buddhist lineage.

Santosha is also one of the focuses of Master Kamalashila’s short, medium-length and long books on meditation (which are all the same book, just at different levels of brevity). He didn’t call it “santosha,” though, because he was Tibetan. But the point was to talk about what you must do if you are to have an effective meditation practice. If you don’t practice santosha, you can’t have an effective meditation practice, because you spend all your time trying to create a satisfactory meditation environment, which is impossible.

Anon 108, if you are going to spell santosha correctly, why not just spell it correctly? The spelling is “?????.” Everyone who reads Devanagari will understand exactly what you mean, but nobody who doesn’t will. So it’s better to use the closest phonetic spelling, which works for looking it up in wikipedia, and which will not confuse any sanskrit scholars, since they are smart enough to know which of the possible words that are pronounced “santosha” you are likely to mean.